Health in humanitarian crises » Hunger and malnutrition »

Chronic malnutrition

- Page updated onOctober 13, 2025

Chronic malnutrition is one of the two existing types of undernutrition, along with acute malnutrition. It manifests in children under five years of age as stunting and is associated with greater vulnerability to infectious diseases and delayed physical, motor, and cognitive development. In the long term, this delay also results in learning difficulties, poorer school performance, and reduced work capacity.

For all the above reasons, this issue has a significant impact on the economy of individuals, their families, and their communities, thereby reinforcing an intergenerational cycle of hunger and poverty. It is estimated to be responsible for the loss of 5%-7% of per capita income in low- and middle-income countries.

Table of contents:

Chronic malnutrition is a multi-causal problem

The dimension of the problem

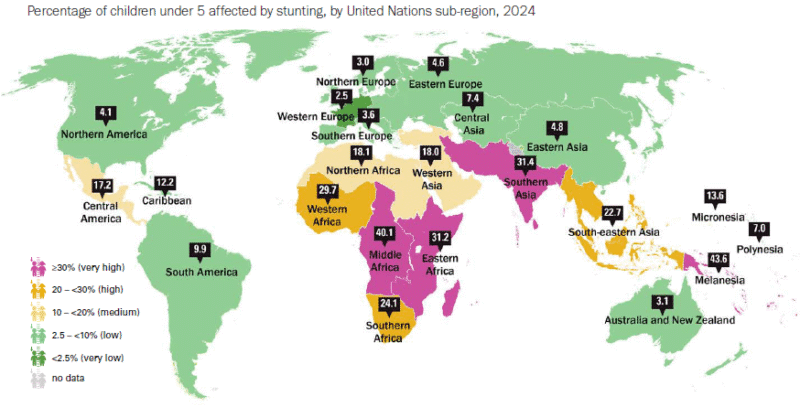

It is estimated that, in 2024, 23.2% (150 million) children under 5 years of age were chronically undernourished. The problem is mainly concentrated in Africa (with a prevalence of 30.3%) and South Asia (31.4%). These values are considered very low when below 2.5%, low when between 2.5% and 10%, medium between 10% and 20%, high between 20% and 30%, and very high when above 30%.

Although the current value of 23.2% represents a significant reduction from the 33% prevalence of chronic undernutrition in 2000, this has not been symmetrical. The decline has been very pronounced in several densely populated South Asian countries, which have experienced the greatest economic growth during the period. However, in Latin America it has been much less pronounced, and in Africa the number of chronically undernourished children has even increased, reaching 64.8 million.

The causes of chronic malnutrition have the greatest impact in the first months of life.

Among the causes of chronic child undernutrition is the continued negative effect of hunger and its social determinants during pregnancy and the first two years of life. This period is known as "the 1,000-day window of opportunity". During this time, food insecurity, limited access to health services, infections, deficiencies in water, sanitation and hygiene, or problems in infant feeding and care practices have a major impact on the development of these children's future potential.

Infections by digestive tract pathogens appear to have particularly high relevance in this type of malnutrition. This is due to enteric dysfunction (atrophy and chronic inflammation of the small intestine), which occurs not only in visible cases of diarrhea but also in cases of subclinical infections.

How is chronic malnutrition defined and diagnosed?

Like acute malnutrition, chronic malnutrition is defined by anthropometric criteria: a height-for-age index two standard deviations below the median of the WHO child growth standard. Children with chronic malnutrition have a shorter height than what would be expected for their age.

This method of measuring chronic malnutrition, although seemingly simple, poses many challenges. To begin with, it requires a properly calibrated height measuring device, a trained person, and the cooperation of the child, who must remain still for a few moments. This is often difficult when the child is in an unfamiliar or even frightening environment. Another issue is that diagnosis depends on age, a detail that sometimes isn’t recalled accurately (especially if the birth took place in the community or if there was no proper birth record). However, the main barrier is that chronic malnutrition is not clearly visible. For example, two girls may appear to be in good physical health and not raise suspicions of chronic malnutrition if one doesn't know that one of them is much younger than the other.

The approach to chronic malnutrition is fundamentally preventive

There is no effective treatment for stunting. It’s simply not possible to recover lost growth and cognitive development over months or even years by taking nutritional supplements. For this and other reasons, the fight against this issue has always been sidelined. However, reducing chronic malnutrition could have a tremendous impact on the economy and future opportunities of the poorest households, their communities, and their nations.

To fight chronic malnutrition, we must address the causes of hunger

Preventive action against hunger and its causes makes it possible to reduce the prevalence of chronic undernutrition, detect it and try to slow its progression during early childhood, and attenuate its consequences. These efforts also include action against acute malnutrition, malnutrition in all its forms, food insecurity, poverty, and inequality.

Preventing chronic malnutrition requires a commitment to peace and environmental sustainability, along with advocacy actions that place it among the priorities of duty-bearers and holders of responsibilities. Additionally, programs are needed to ensure access to food, water, sanitation, hygiene, and health services in humanitarian crises, support programs for families and caregivers with a gender perspective, and comprehensive systems of universal social protection for all people, especially the most vulnerable.

Although it is a priority for these actions to focus their effects on pregnant women, children under 2 or 3 years of age and their families, the "thousand days" is not the only window of opportunity. Growth does not stop at age 2. On the contrary, in adolescence there is a second period of accelerated development, which should be used to make up for the previously accumulated delay. In this period, moreover, the risk of developing overweight and obesity also increases, if the diet is not adequate.

Hunger and malnutrition

External links

- UNICEF, WHO, World Bank Group, 2025. Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates.

- Acción Contra el Hambre, 2023. Malnutrición crónica: marco de acción para un abordaje preventivo y multisectorial.

- UNICEF, 2017. The Adolescent Brain: A second window of opportunity.

- World Bank, 2017. An Investment Framework for Nutrition: Reaching the Global Targets for Stunting, Anemia, Breastfeeding and Wasting.

- WHO, 2016. Childhood Stunting: Context, Causes and Consequences Conceptual framework.

- De Onis, 2016. Childhood stunting: a global perspective.

- Prendergast, 2014. The stunting syndrome in developing countries.